03 September 2022 / 3-Min Read / Translate

If you ever watch great squash players playing a match, you’ll notice how smoothly and quickly they move. It’s like dancing, but instead of the dancers working together, they are working against each other, although they do cooperate. One thing you might notice is that they seem to walk back to the T after they hit the ball, not run.

Let’s explore that for a moment. What’s the difference between running and walking? Do you know? It’s not the speed. Walking has one foot on the ground at all times, whereas running doesn’t. There’s actual moments when running where both feet are off the ground. So what, I hear you cry. Running means you get back to the T faster, right? Well, when you have both feet off the ground, you can’t change direction. I’ll be honest though, the “running” I am talking about isn’t the same as running on a court – you just don’t have the time or space to do that when rallying at the back. But, the general concept is valid and useful.

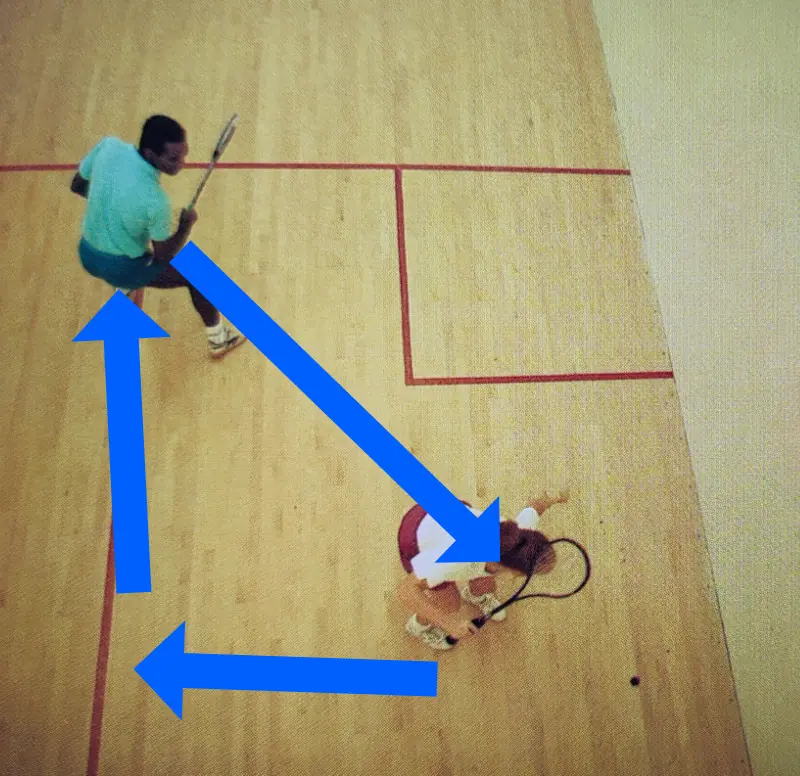

Let’s look at it from the balcony. Here you can see two players. One is one the T waiting for the shot, the other is in the righthand back corner and is about to play a straight drive. Notice that the player on the T is slightly over to the right side, that’s partly because he knows the other player is going to hit straight and partly because being slightly closer to the side wall is fine.

The moment the player in the back hits the ball, she will move towards the half-court line and then move forwards towards the T. The player on the T will have clear and direct access to the ball. This circling goes on when the drives are straight. if the player in the back corner were to hit a crosscourt, the player on the T, would make the same movement towards the ball as if it were a straight drive. The striker, would be able to move directly back to the T position.

As the striker hits the ball, the followthrough may provide some momentum to begin the movement back to the T. The striker will be facing their opponent and watch them in case they decide to volley the back. The moment the shot has been played, the striker’s attention moves to their opponent – they don;’t just stare at their shot.

There’s an inherent challenge/counter-challenge going on here and in all similar rallies. Each player is trying to hit a shot that won’t lose them the point, but will cause their opponent to hit a weak return. This is done, but hitting as close to the side wall as possible, but also by varying the height and speed of the shots to hopefully cause their opponent a miscalculation.

Rallies like this can go on for quite some time and they are mental rallies as much as physical ones. Rallying like this is not very tiring, so it’s not that players are trying to tire out their opponent. They are trying to break their discipline and resilience. That’s why sometimes the first game can be close, but then the next two are easy. The winner has broken the player mentally – that’s a little exaggeration, but a close explanation.

In the same way that Boast and Drive is probably the most common drill, the length-only game is probably the most common condition game. They both address basic movement around the court. To play the length-only game, play everything to bounce behind the short line. If it hits the line, it’s out. It should be the first bounce, not the second, that’s a different game entirely.

This game allows you to develop your hitting skill and movement. Be sure to go right back to the T otherwise you will keep bumping into your opponent.

You will need to practice to make circling look and feel natural. a lot depends on your ability to hit deep enough shots to ensure you opponent has to go into the corner. Try to hit and move immediately, and watch only when you are moving. No hitting and staring at your shot.